While visiting Mammoth Lakes at the end of August 2016, we took a 180 mile adventure day ride and made a nice loop north stopping at one of my must-see places, Bodie ghost town. After seeing some friend’s photos on Facebook, I had to see it for myself. There is so much history in that little town and it’s a miracle it’s all still there. Bodie sits at 8379 feet elevation and is subjected to dry, warm summers as well as heavy snowfall in the winter. Combined with the high altitude and a very exposed plateau, the town can get winds at close to 100 miles per hour. Although it’s a protected historical site and obviously receives some occasional maintenance, it’s still crazy those old buildings are still standing.

While visiting Mammoth Lakes at the end of August 2016, we took a 180 mile adventure day ride and made a nice loop north stopping at one of my must-see places, Bodie ghost town. After seeing some friend’s photos on Facebook, I had to see it for myself. There is so much history in that little town and it’s a miracle it’s all still there. Bodie sits at 8379 feet elevation and is subjected to dry, warm summers as well as heavy snowfall in the winter. Combined with the high altitude and a very exposed plateau, the town can get winds at close to 100 miles per hour. Although it’s a protected historical site and obviously receives some occasional maintenance, it’s still crazy those old buildings are still standing.

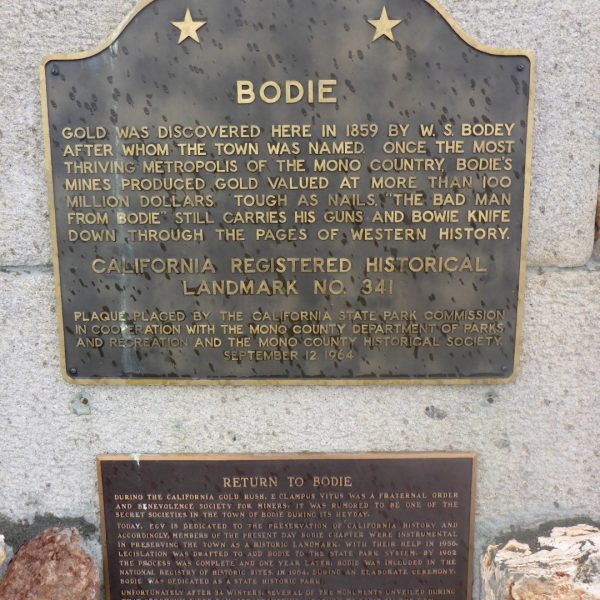

Bodie began as a little mining camp after the discovery of gold in 1859 by a group of prospectors, including W. S. Bodey, who perished in a blizzard the following November while making a supply trip to Monoville, never getting to see the rise of the town that was named after him. According to area pioneer Judge J. G. McClinton, the district’s name was changed from “Bodey,” “Body,” and a few other phonetic variations, to “Bodie,” after a painter in the nearby boomtown of Aurora, lettered a sign “Bodie Stables”.

In 1876, the Standard Company discovered a profitable deposit of gold-bearing ore, which transformed Bodie from an isolated mining camp, comprising a few prospectors and company employees, to a Wild West boomtown.

By 1879, Bodie had a population of approximately 5000–7000 people and around 2,000 buildings.

One idea maintains that in 1880, Bodie was California’s second or third largest city. Over the years, Bodie’s mines produced gold valued at nearly $34 million.

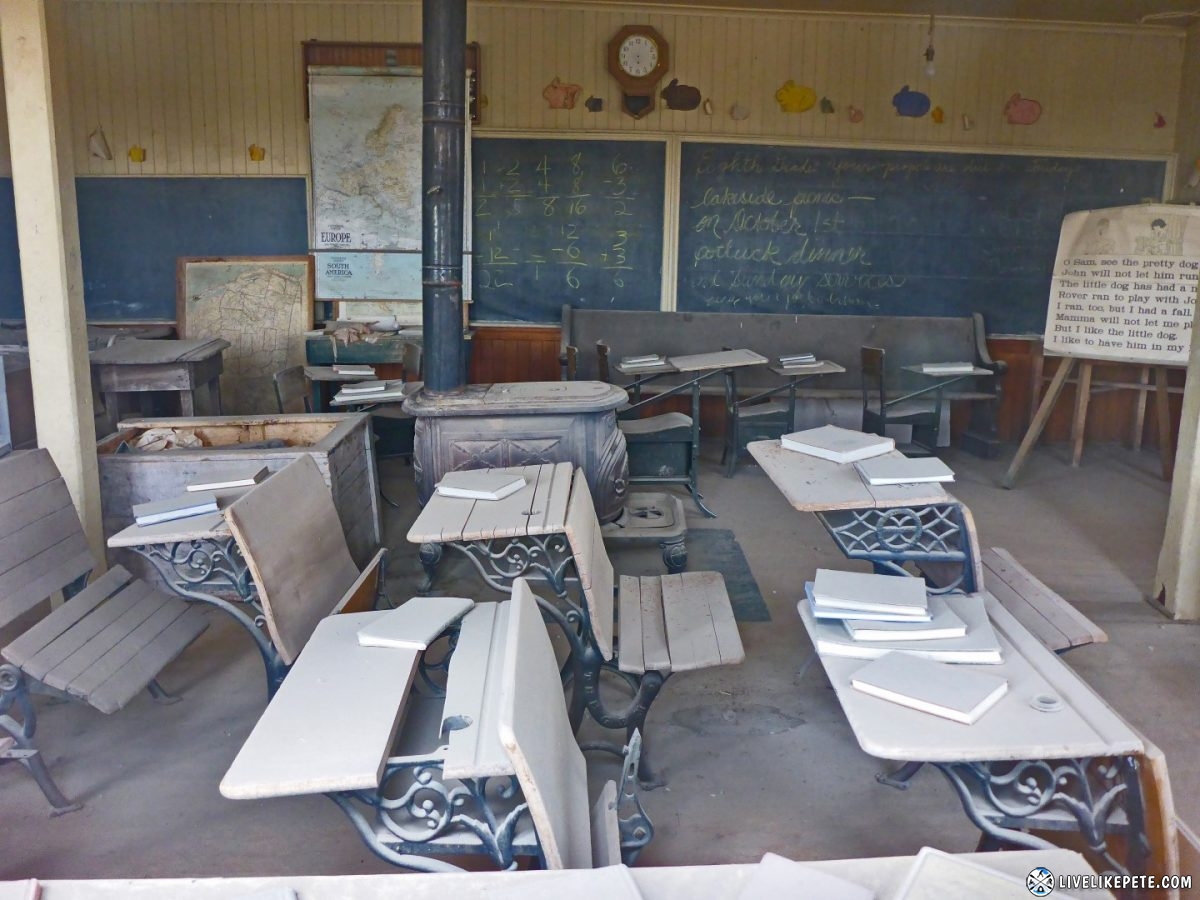

As a bustling gold mining center, Bodie had the amenities of larger towns, including a Wells Fargo Bank, four volunteer fire companies, a brass band, a railroad, miners’ and mechanics’ unions, several daily newspapers, and a jail. At its peak, 65 saloons lined Main Street, which was a mile long. Murders, shootouts, bar room brawls, and stagecoach holdups were regular occurrences.

The first signs of decline appeared in 1880 and became obvious towards the end of the year.

Promising mining booms in other nearby towns lured men away from Bodie. The get-rich-quick, single miners who originally came to the town in the 1870s moved on to these other booms, which eventually turned Bodie into a family-oriented community. Two examples of this settling were the construction of the Methodist Church (which currently stands) and the Roman Catholic Church (burned about 1930) that were both constructed in 1882. Despite the population decline, the mines were flourishing, and in 1881 Bodie’s ore production was recorded at a high of $3.1 million.

In 1912, last Bodie newspaper, The Bodie Miner, was printed. In 1913, the Standard Consolidated Mine closed. Mining profits in 1914 were at a low of $6,821.

In 1917, the Bodie Railway was abandoned and its iron tracks were scrapped.

The last mine closed in 1942, due to War Production Board order L-208, shutting down all nonessential gold mines in the United States. Mining never resumed.

The first label of Bodie as a “ghost town” was in 1915. In a time when auto travel was on a rise, many were adventuring into Bodie via automobiles.

The San Francisco Chronicle published an article in 1919 to dispute the “ghost town” label. By 1920, Bodie’s population was recorded by the US Federal Census at a total of 120 people. Despite the decline, Bodie had permanent residents through most of the 20th century, even after a fire ravaged much of the downtown business district in 1932.

A post office operated at Bodie from 1877 to 1942.

In the 1940s, the threat of vandalism faced the ghost town. The Cain family, who owned much of the land the town is situated upon, hired caretakers to protect and to maintain the town’s structures. Martin Gianettoni, one of the last three people in Bodie in 1943, was also a caretaker.

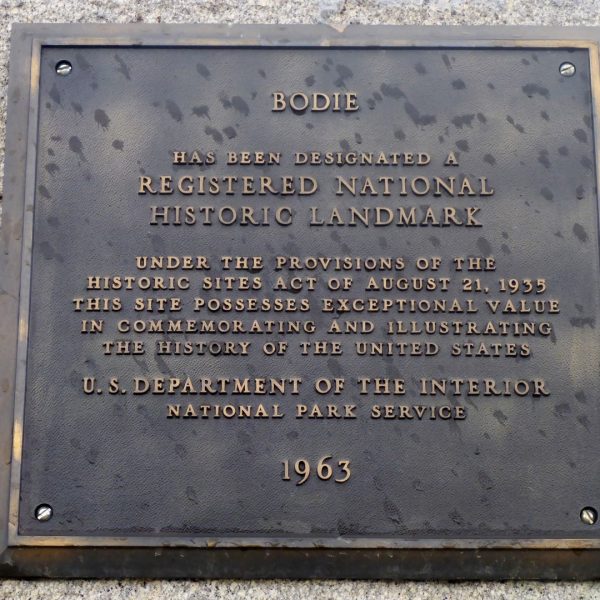

Bodie is now an authentic Wild West ghost town. The town was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961, and in 1962 it became Bodie State Historic Park. A total of 170 buildings remained. Bodie has been named California’s official state gold rush ghost town.

Today, Bodie is preserved in a state of arrested decay. Only a small part of the town survived, with about 110 structures still standing, including one of many once operational gold mills. Visitors can walk the deserted streets of a town that once was a bustling area of activity.

If you have the chance to go see Bodie for yourself, do it! Make sure you have several hours to explore the whole town and even the outskirts. Bring some comfortable shoes, a snack and some water. Don’t forget a camera too! It’s a photographer’s playground.

All photos © Pete Greep

Leave a Reply